License: CC0, Source: https://www.maxpixel.net/Together-Hands-Team-People-Unity-United-Teamwork-1917895

For years now, the concentration of wealth and power into too few hands has bothered me. That it gets progressively worse with so little action to address this is even more troubling. Why? Because such lopsidedness creates an inherently unstable system state. Historically, even the most resilient of systems break when wealth inequality becomes unsustainable. Increasingly, the have-nots resent being forced into a system in which the barriers to success are so high. Nonetheless, these trends continue.

There are those who see no issue with the status quo, and a minority may view it as morally justified. Conversely, there are others who think nothing less than a full scale teardown and replacement of the private property foundations of capitalism is what’s required. Neither of these options are viable, but there must be a way out of this mess.

I’m not big on pontification or mental exercises, though I admit someone has to fill those roles. I’m a pragmatist. I’m a fan of getting things done. While grand sweeping changes can feel better in a thought exercise, it’s more often small incremental changes that cause major lasting changes. Anyone who’s visited the Grand Canyon can attest to the power of small changes that add up to big ones over time. An obese person could lose 50 pounds by going on a diet that prescribes a mild caloric deficit and exercise over a year. They might gain the same results by getting liposuction, or, in a more drastic example, by amputating a limb. That last one obviously serves as an example of emphasizing the wrong parameter—and profoundly so. The point is, the small incremental changes can lead to bigger ones, and often with less overall turmoil. Additionally, small changes over time become a habit, a way of being in the world with an assumed set of priorities and assumptions that become self-reinforcing. Now, those changes naturally resist reversion to the old attitudes that caused so many problems in the first place.

Accepting this as a foundational principle, I thought hard about it for a while and read a few hopeful anecdotes, but only recently was I introduced to a world of people taking this incremental approach regarding ownership of the economy. This approach isn’t some theoretical, historical, or “unicorn” idea. It’s a real thing at work in the world at this very moment. It is a concept of distributed ownership of companies some call “Capitalism 2.0”. It’s about using cooperative corporate structures to put real power in the hands of a company’s workers, customers, content producers, or the communities built around that company.

While this approach is gaining momentum, it doesn’t yet have critical mass, and it hasn’t become the default economic model, a fact made obvious by a continually widening wealth gap. If this model—one of distributed ownership—solves so many problems, why hasn’t it prevailed? What would allow it to do so? Those are some things I want to explore more and discuss a bit here.

I come from an entrepreneurial family. More relevant to this conversation is that I’ve started a business I later sold only a few years ago. Building it for sale wasn’t my ultimate intention, so I always structured it and ran it for long term sustainability. I’ve also invested time and money into other businesses at various stages, from initial formation to firms several years old that were interested in taking things in new directions. I’ve even dabbled with the idea of starting another company one day if the circumstances are optimal. In all of these ventures, I’m always sensitive about their cultures. I’m looking for companies that have sustainable business models, not those whose only path to success is rapid pump up to acquisition or going public. I’m looking for a company that takes a holistic approach about the health and benefit of its team members, customers, and community, not one that’s pathologically interested only in maximizing shareholder value. It’s even better when that company has an ownership or profit sharing system so the fruits of everyone’s labor can be shared broadly, and not only with a small handful of owners or investors. While this has always been my modus operandi I think I can do a much better job of “walking the walk” on distributed ownership than I have in the past.

Were I to wave a magic wand, I’d love to create a world where nearly every business is owned and operated by the people who comprise that enterprise—the workers themselves. I’m not talking about a token few hundred or thousand dollars’ worth of shares in a multi-billion-dollar company. While that does tie the fortunes of the employees to the health of the business in a minor way, it’s hardly enough to affect the way business is done. What I’m suggesting goes beyond token stock ownership or profit sharing to get at a form of true ownership. True ownership means nothing less than this: the distribution of the economic benefits of that enterprise, as well as the management responsibilities for that enterprise, across the entire workforce.

When we talk about “business,” we often conjure images of mega-corporations like Amazon—behemoths with top-down management that has a massive effect on employees, with ripple effects that touch everyone with whom those employees interact. This perception about what constitutes “business” is wildly inaccurate. There are far more examples of small businesses than mega-corporations, and these businesses are more like personal endeavours, labors of love and profit that individuals work hard to support and maintain. In this hypothetical world of distributed ownership everything from Amazon to a “mom-and-pop” enterprise of only a dozen people would be substantially owned and controlled by those who are a part of it.

So how does one get from today, where a distributed ownership structure is rare, to one where it’s the predominant form of capitalism? That’s the topic I’ve been wrestling with for the past year or so.

Let there be light

At the beginning of April, I was on my first post-COVID trip when I got an idea. Trips always get my brain going for two reasons. First, it gives me idle time away from the internet and the daily distractions of work. Secondly, it gives me time to work through hours of podcast backlogs. It was while waiting in an airport that my brain wouldn’t put down this fascination with how I’d formulate a company profile that would be effective, while also distributing ownership to most team members. How would I create a more distributed management profile to bring the concerns of the various divisions together, especially if I started the company with only one or two people that would then have to grow intentionally to incorporate more and more feedback? How would we avoid analysis paralysis?

After a few hours of idle thinking and jotting down salient points, I scribbled this in my notes: “There’s no way I’m the first person that has tried to figure this out.” That leg of my trip was over and that was that. On the return flight, however, something interesting happened.

With the background noise of this more equitable economic model in my mind, I started up a Planet Money podcast called “Socialism: 101” . I figured it’d be tangentially related to my thoughts about distributed ownership, at least in so far as it would speak to an alternative way to handle the equity problem. So while it wouldn’t be a complete distraction, it wasn’t likely to address the core concepts I was thinking about, which was how I’d set up an organization for that purpose. That was the totally wrong take. The podcast was addressing exactly what I was trying to accomplish. In this country and many other places, we think of socialism as a monolithic, centrally planned creature wholly bound up with an enormous and bureaucratic state. What the podcast was talking about used similar words (workers owning the means of production), but in precisely the same sort of distributed ownership structure I was trying to accomplish. The more I listened, the more energized I got by the concept. I wanted to learn more. I started making notes of things to research when I got home. Then, the next podcast came up in the queue.

The next podcast was a Rework podcast on the topic of: “Coops: The Next Generation” . The terms “coop” and “cooperative” were the same I’d heard a bunch in the previous podcast. Now here were Jessica Mason and Greg Brodskey , who were talking about coops in general and an accelerator they’re a part of called Start.coop . I couldn’t believe my luck. Now we were really getting down to some details about doing this for real in the present day, complete with ideas for how to start such companies from scratch. The patently obvious thought from before—that others had tried figuring this out—was right. They’d even begun addressing some of the problems presented by trying to bridge the present world, where investment capital drowns everyone else out, with the more equitable world, in which investment capital is needed but can’t be the driving force. Armed with all these new concepts, I was ready to dive in!

On nomenclature: why call it “Capitalism 2.0”?

Purely for marketing purposes, I’m deliberately calling this area of development “Capitalism 2.0” and not “socialism.” This is despite the fact that the terms often discussed by socialism are nearly identical. Stripped down to basics, the central idea is that of workers and/or communities owning the means of production. However, the word “socialism” in the United States is toxic, and likely beyond repair. Most Americans—especially older Americans who remember the Cold War—are entirely unable to give the term “socialism” a fair hearing. This is the artifact of decades of Red Scare propaganda from the 1920s through the end of the Cold War. In our current era, members of Democratic Socialist parties have to constantly explain themselves whenever they encounter anyone outside true-blue liberal bubbles. The term “socialism” is quite literally used as slander for everything from single payer health insurance to a company that voluntarily decides to pay living wages . My favorite meme that encapsulates this dynamic is this:

In contrast to this knee-jerk rejection of “socialism,” support for broader ownership by employees, even in the United States, is very high. 69% of Americans would like to institutionalize the right of workers to purchase their workplace in the event of a sale. Only 20% oppose a policy that companies with more than 250 employees need to put 10% of the ownership into a workers fund link . If the idea is good, I don’t want to complicate it with a potentially off-putting moniker. If you were in a restaurant and saw “strips of cattle iliopsoas muscle intentionally decayed for 30 days” on a menu, you’d probably start looking for the exit. However, “filet mignon dry aged for 30 days” makes a meat eater’s mouth water. That explains why I chose not to use the s-word.

But why did I choose to keep the c-word (capitalism)?

Although this is slowly changing, in this country, our love and acceptance of the term “capitalism” expresses an almost mirror image of our contempt for the word “socialism.” Our very loose—and that’s putting it mildly—understanding of the term “capitalism” is comparable to our tenuous understanding of “socialism.”Referencing the above meme, Norway is “capitalist” when it’s convenient and “socialist” when it’s not. If someone asks if I’m pro-capitalism, my answer depends entirely on what they mean. If they mean a market based system of freely associated people and organizations exchanging goods with private ownership, then yes, I support that. If you mean a system that allows 80% of the wealth to be in the hands of 1% of the population, one that has most people working in substandard conditions for substandard wages, and with a sole focus on “maximizing shareholder value” regardless of the effects on everything else, then no, I don’t. However, even though “capitalism” is a “good” word in our lexicon, all but the most extreme people acknowledge that it nonetheless needs some major work. Add to that the fact that without the baggage of the term “socialism,” the overwhelming majority believe that more ownership by more people is a good thing, I’m going with “Capitalism 2.0” as the moniker for these articles.

It’s not just theoretical

As I stated above, I want to work on concrete, real world things. While it’s true that modeling and imagining the art of the possible, and conjuring utopias and methods by which to reach them has a place, it’s not my primary goal here. I spend time thinking about those things for short fiction work I do, but my main goal here is to work to make this the default economic model in the future. On that front, the good news is there’s a long, vibrant history of these sorts of corporate organizational systems in the form of cooperatives. The first cooperative in the United States predates the formation of the country by several decades. Benjamin Franklin started the Philadelphia Contributorship in 1752 (link ). While it isn’t a foreign form, the cooperative is definitely not our standard corporate form. In fact, even if cooperatives didn’t have the obstacle of reorienting workers toward cooperative, lateral management systems, current business law makes it more complicated to form cooperatives. That doesn’t mean there aren’t great examples of cooperatives in action that show it works in practice and can scale from a few dozen people to a multi-billion dollar organization.

By far the most used example of a cooperative is Mondragon Corporation , out of Spain. Founded in 1956 by José María Arizmendiarrieta , It has, over time, spawned many sub-coops and become a multi-billion dollar corporation with over 81,000 workers, most of whom are owners as well. It’s the go to example specifically because it achieved such a large scope and size. It bucks the notion that cooperatives are about the hippie food store down the road (which is a consumer cooperative, not a producer cooperative), or something for non-industrial/technology industries. While Mondragon is an example of a worker-owned cooperative that started from scratch, that isn’t the only model of cooperative structures.

As mentioned above, cooperatives can also be about members of the community or consumers. Ace Hardware is a retailer cooperative operated in the United States. Until researching this, I assumed Ace Hardware operated under a franchise model. In reality, it represents the world’s largest hardware retail cooperative. The cooperative members in this case comprise the various hardware store owners who leverage economies of scale for purchasing supply and other things through the cooperative. This conglomeration of independent entities is a hallmark of the cooperative formula for industries like agriculture and energy. The previously mentioned Philadelphia Contributorship is an example of a cooperative of customers, though having been a customer of theirs, I certainly never realized I was part of the cooperative in any meaningful way, similar to how most GEICO customers likely feel about that company.

One last example I want to bring up is how cooperatives are occasionally used to save a failing business. Businesses fail all the time. The most frequent outcome of these business failures is that a “Vulture Capitalist” firm from outside the industry swoops in and buys these distressed assets but not their debts. The new owners then slash staff to make these businesses seem more profitable before selling them on, but often, they take a different path. In the most extreme cases, the new owners lay everyone off and strip the company for its more valuable parts, selling those aspects (real estate and intellectual property being the most common) for scrap. This is what happened when Republic Windows and Doors began to struggle to make profits in 2012. They’d had a previous brush with death in 2008 when Bank of America cut off their line of credit. This time, there was no reprieve. The company was closing for good. Normally, that would have meant laying everyone off and selling the company machinery. This time, something else happened. The workers collectively sought and secured financing to buy the factory for themselves. They organized it into a worker cooperative that’s still operating today. Their website details their story with a lot more detail.

Advantages of Capitalism 2.0 over traditional capitalism

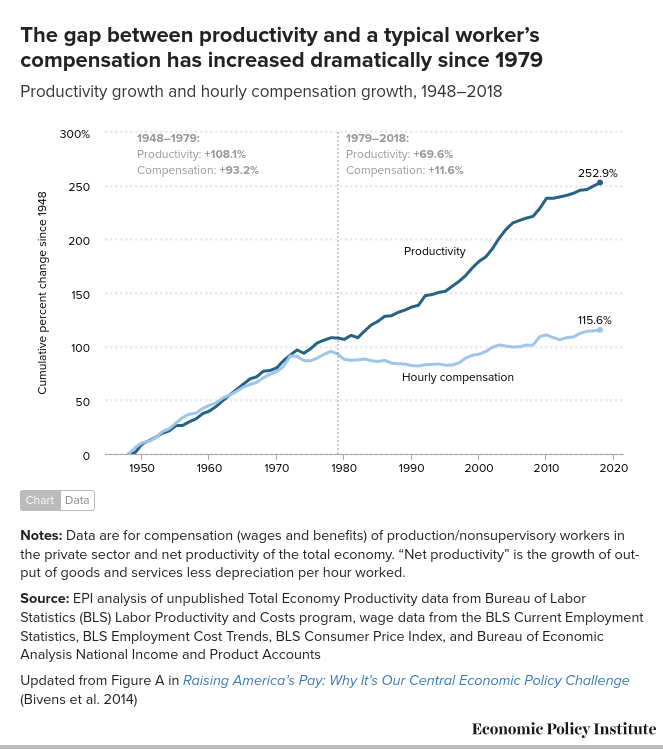

A new era of capitalism rooted in employee and/or community ownership is far preferable to the capitalism of the present day, primarily because the biggest benefactors of the outputs of these companies will be the people who operate or are serviced by those companies. Had this model been in place as the dominant corporate structure, we likely would never have experienced the divergence between productivity and hourly pay known as The Productivity Gap . What is the productivity gap?

Starting in the 1970s, while economic productivity continued a linear and expected growth curve, real wages didn’t rise in concert with that increased productivity the way they had since the post-war 1950s. Instead, they first leveled off, then began regressing. It wasn’t until the late-1990s that they once again began to increase, though even once they did, it was along a much shallower slope than that of overall productivity, see below figure:

Figure 1: Productivity Gap 1948-2018 (Source: Economic Policy Institute)

The distance between these curves has only gotten more exaggerated as time has passed, and the gap widens most crucially during economic downturns. While it’s possible wages themselves may or may not have changed dramatically in a cooperative dominated world, the profits would have been much more equally distributed to worker-owners instead of going almost exclusively into the pockets of shareholding billionaires and millionaires. There are more than mere economic reasons why the former is better than the latter.

One of the problems with most corporate structures, especially in the United States, is that worker’s voices are too frequently absent from the decision-making and management processes. When they are factored in, it’s often in the forms of pseudo-anonymous surveys or reading the tea leaves of the worker’s reactions to company policies. When larger changes are necessary, such as when the working stakeholders of the company face layoffs or big pay cuts to survive a temporary downturn, worker-stakeholder voices are practically non-existent. A cooperative structure gives them a voice far superior to the one they possess under the present status quo—and this includes the status quo with unionization. Unions in this country create a dichotomy of “us” (the workers) versus “them” (the owners and management). It isn’t entirely artificial though. The workers aren’t the owners. The workers don’t share in the rewards of the business, but they are also often shielded from many of the responsibilities of the business of which they should otherwise be a part. The cooperative structure breaks down these barriers because the workers are the owners. The workers aren’t a temporary “resource” that exchanges hours for money. They’re given a specific voice in decision-making processes. That doesn’t mean every minute decision requires a vote by everyone in the company. It does mean the other organs of the business and/or community are represented within the organization, and it gives real power to the members of the whole team instead of reserving such important life-changing and community-altering decisions to the limited experiences and motivations of a handful of executives and owners.

The end result of that is often better, not just for the workers, but also for the longer term health of the companies themselves, especially during economic downturns. This article points to the fact that during the 2008 crash in the UK, cooperatives outperformed general economic growth by a factor of two. In the case of companies that give their employees a decision in difficult layoff or wage reduction deliberations, the end result is often more to the latter (wage reduction), but in a way that ultimately made the company healthier when the economy picked up. Last year, at the beginning of COVID Gravity Payments’ CEO Dan Price asked the employees to vote on voluntary temporary pay cuts versus layoffs to survive the downturn. 98% of the workers stepped up, some voluntarily cutting their own pay 30-50%, link (here ). It created enough economic momentum after the brief downturn that everyone eventually received compensation for their temporarily cut wages and the company continues to grow through the COVID mess. Under traditional corporate models, that decision would have been made in isolation from the worker stakeholders, probably resulting in lots of layoffs. No, Gravity is not a cooperative, but these sorts of behaviors are seen in cooperatives because the workers are empowered in reality, not just in some marketing slick sheet.

Ah, the cooperative is inevitable… or not

Since Capitalism 2.0, with its distributed ownership model, is the most amazingly perfect business structure in the world, it will of course take the world by storm, displace the existing dominant model! Right? It likely comes as no surprise the answer to that question is an emphatic “no.” As I mentioned, cooperatives and similar structures have been here since before the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Cooperatives are created all the time. Since the business form isn’t novel, why isn’t it more pervasive?

Some simple answers to that specific question begin with historical baggage created during the mid-20th century Red Scares. Until World War II, the US government had programs that promoted the creation of cooperatives. After World War II, we slammed the brakes on this line of thinking, as it sounded far too “pinko-commie” for a population primed to resist the ideas of the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, these cooperative forms were reexamined by members of racial minorities who found themselves cut off from full economic agency in a world where black people couldn’t get loans. Famously, many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) communities were subjected to the practice of redlining—denied loans and precluded from serious consideration when they attempted to purchase homes in burgeoning suburbs and preferred neighborhoods within cities. Furthermore, they were often discriminated against in the business world, kept from buying into franchises and qualifying for business loans. When the racially dispossessed turned to cooperatives, that added fuel to the accusations that cooperatives were indicative of an uber-leftist, anti-American movement. Nothing could have been further from the truth, however: cooperatives are as American as apple pie. Meanwhile, though the language and attitudes regarding cooperatives are no longer as explicitly linked to communism these days, the artifacts of those anti-communism arguments remain extant in the minds of Americans who lived through the Cold War.

The first artifact of that fall out is the lack of awareness that these cooperatives exist. I’ve been going to an Ace Hardware store for years, and in all that time, I never realized it was a cooperative venture. I’ve been a member of mutual insurance companies and not once did I realize what that meant. Before this research, if you used the word “cooperative,” I would have pictured the hippie natural food store down the street (a strictly consumer cooperative) and that’s it. Raising awareness of these structures and how not so novel they are will be a big part of normalizing them, but that only gets us so far. We need to have better education about how to do these things, though.

As I’ve said, I grew up in a family of small business owners. I’ve started my own small businesses. I’ve been an investor and/or advisor in several other small businesses as well. Along with a formal advisory role, I’ve given tons of informal advice for friends and family who have looked at starting businesses. Despite that level of experience in “business,” I have very little practical knowledge about how I’d start a cooperative business structure. Before last month, I thought I’d mostly have to figure it out from scratch using analogous structures. Searching online, I find hundreds of links and sources for how to start a non-cooperative business structure. Making access to similar types of resources for cooperative ventures readily available will be vital to making them more pervasive business structures. Knowledge alone isn’t enough to start a business; a good model for any business structure also needs supportive resources.

Until recently one of the biggest bridge problems was getting financing for a cooperative. Traditionally, cooperatives pooled resources to create a bootstrapping initiative from which they could grow. That can work to a certain extent, but it obviously requires people to have those resources to pool to begin with. That means traditionally marginalized groups are often marginalized from access even to small sums of capital vital to starting the process. In many industries, companies need access to a significant amount of startup capital in order to have any hope of becoming stable. Traditionally, such investment capital has come from venture capital firms that swoop in with startup funds in exchange for large chunks of ownership. Such venture capital firms invest in many different startups, expecting that, despite multiple failures, many of the firms in which they invest will coast toward viability, at which time they can sell their ownership of the business for a sum equal to ten times their initial investment or more.

Until recently, cooperatives have had no access to the building blocks of this “angel investor” model. Specifically, they don’t—and in a traditional cooperative ownership model, can’t—have multiple classes of shares venture capital firms require in order to function. Recently the laws have changed, and several groups have come up with ways to get investors into cooperatives without upsetting the balance of power of the cooperative ownership, as well as getting beyond the mindset of traditional venture capital processes, which depend on acquisition by a larger firm or an initial IPO. Greg Brodsky’s two-part series on investing in startups covers a lot of that ground, Part 1 here , and Part 2 here {:target="-blank"}. Right now, the amount of money being poured into these sorts of companies is miniscule compared to the sums being thrown around in the traditional startup world. Changing those dynamics will be a big part of changing the distribution of ownership structures to such that they tilt more heavily toward cooperative/distributed ownership.

My personal path forward

What can we do to make this sort of thing a reality? I can only state what I’m going to do for the time being. The first thing I plan to do is to get involved in financing cooperative startups. With accelerators like Start.coop or Zebras Unite , there are some interesting avenues opening up to accredited investors. Getting involved with those organizations could also be an opportunity to help with the mentorship of those companies as well. Secondly, I want to do more advocacy on this issue. As I learn more, I intend to share what I learn here and elsewhere. Just as with my coding tutorials, in which I explore new technologies, my efforts here may serve to be instructive for other newbies in the arena, allowing them to see someone else go through the ramping up process. Lastly, if I ever get to the point of starting another company, I intend to apply all the principles learned here to create a cooperative ownership structure from day one. Part of what appeals to me about working with organizations like Start.coop or Zebras Unite is that I can see the real world aspects of cooperatives in practice. I can use that information to help move my own hypothetical company forward.

In one of the podcasts, someone described the excitement behind these ideas as “wanting to have front row seats to Capitalism 2.0.” Though I initially liked that sentiment, it has too much passivity about it, as if my only role is that of an observer. I want to be more than that; I want to be embedded in the process of making Capitalism 2.0 happen.

Conclusion

This is only the beginning of an exploration toward a concrete process that can make our current system far better and far more equitable to much more of the population. I started this thinking I’d have to start mostly from scratch. While I’m pleasantly surprised there’s already so much activity going on in this space, I’ve also found I have more questions than when I started. Some of those questions have no answers yet. Sometimes they have no answers because there will never be only one true answer to that question for all scenarios. In other cases they have no answers because a good solution hasn’t yet been tried and shown to work. As I keep exploring and begin the doing of Capitalism 2.0, I hope to find some of these answers and perhaps help to formulate potential answers to many of the rest. There’s an infinitesimal chance I’d live to see such a radical transformation in the economic system in my lifetime, but if I could lay some seeds and in the process make some people’s lives a lot better, it would be a worthy endeavour, even if such a larger systemic change never came to be.

For more reading check out Everything for Everyone by Nathan Schneider .

A special thanks out to my friend Chet who did a lot of work editing and massaging my original stream of consciousness material into this very polished state.

2021-05-20

in

2021-05-20

in

23 min read

23 min read